The other Russian war the world forgotDue in part to Russian intervention, the Syrian Civil War has gone on for more than a decade. Reporting from the Turkish-Syrian border, we talk to Syrians about what it means to persevere.TIM MAK AND ALESSANDRA HAY

19/11/2023

Editor’s note: I’m totally burnt out after my latest trip to Turkey (coming from Kyiv requires more than two days of travel). So we are going to skip our midweek issue, and return with our next issue next Sunday Nov. 26.

Ali Hajj Zakour was at work, manufacturing ceramic tiles, when a neighbor called.

His home had been hit by a Russian airstrike.

He rushed home to find his mother and sister dead, and his home ablaze.

It gets worse. The two had been taking care of his son, then just three years old. And he was still inside the burning building. Ali rushed in and managed to find his son’s body, carrying it out of the smoke-engulfed room.

The child was still alive, if barely, and they rushed onto an ambulance to take him to Turkey.

Mohammed, as he had named his son, “died and returned to life,” Ali now recalls. The child was in a coma for three and a half months. He had sustained burns over 70 percent of his body.

"It was a big disaster,” Ali said. “Everything has gone away. Nothing remains.”

His son has been forced to endure nineteen surgeries over the past five years since the attack. We met in the House of Healing, a charitable initiative in the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep, where Syrians can receive medical help.

Ali, left, with his son Mohammed at the House of Healing in Gaziantep, southern Turkey.

Ali, left, with his son Mohammed at the House of Healing in Gaziantep, southern Turkey. There’s a strange and terrible unity between Ukrainians and Syrians, one they never wanted. And that is their awful kinship as victims of Russian bombardment and atrocities. Russian intervention in both places led to displacement, horrific injuries, and death.

"They are the same as us. God be with them,” Ali proclaimed. “We both receive the same missiles, the same attacks from the Russians."

It struck me, as I was speaking to Syrians, that the day Putin dies would be a celebration not only in Kyiv and Odesa, but also one of partying and rejoicing in places like Idlib and Aleppo. Putin’s military intervened in Syria on the side of the Assad regime eight years ago, and regularly bomb rebel forces with impunity.

“We hope that day will come soon,” one Syrian refugee told me. “We hate Putin more than Bashar al-Assad. We were fighting for freedom in our country. Why did [Putin] come to our country? Why did [he] come to help Bashar al-Assad, the dictator? … Without Putin, Assad would have fallen years ago.”

As of last year, the United Nations agency for human rights estimated that more than 300,000 civilians have been killed since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011 with demonstrations demanding democracy and the ouster of the autocrat Bashar al-Assad.

But if Ukraine risks being forgotten in the Western press, the Syrian Civil War receives even less coverage. Over the last decade an average of 84 civilians have died every single day, many of them as a result of Russian airstrikes or bombardment.

“They are killers. They kill everywhere,” said Ali. “Five of my neighbors’ children died due to Russian airstrikes.”

Unlike their Ukrainian counterparts, Syrians don’t have air defenses. They don’t have early warning alerts for incoming planes. They have no air force, no Javelin missiles, and little Western assistance. The world has long forgotten them.

There’s no app when missiles are incoming. The average Syrian is forced just to listen for planes overhead as a hint that warplanes are coming. Syrian children are terrified when they come into southern Turkey for medical treatment, because they think commercial airliners are a sign that there will soon be explosions nearby.

So it’s no wonder that Mohammed is a shy child, one who wasn’t particularly interested in making eye-contact with the strange foreigner with a microphone. His face and hands bear the marks of his traumatic early life, with burns on his young feet and hands and face.

The scars are a constant reminder of the trauma he’s been through, not to mention the anti-inflammatory medications he takes (and will have to take for the rest of his life) due to the permanent damage in his lungs.

“My son is like any other child,” Ali told me. “He likes to play with other children. He likes to study. He loves studying so much.”

Now you might think this is the exaggeration of a proud parent. But Mohammed himself proved this to me. When I went to interview him, the eight-year-old began to cry desperately. He had been pulled from an Arabic-language class where they were learning letters, and he wanted nothing more than to be back in the room learning.

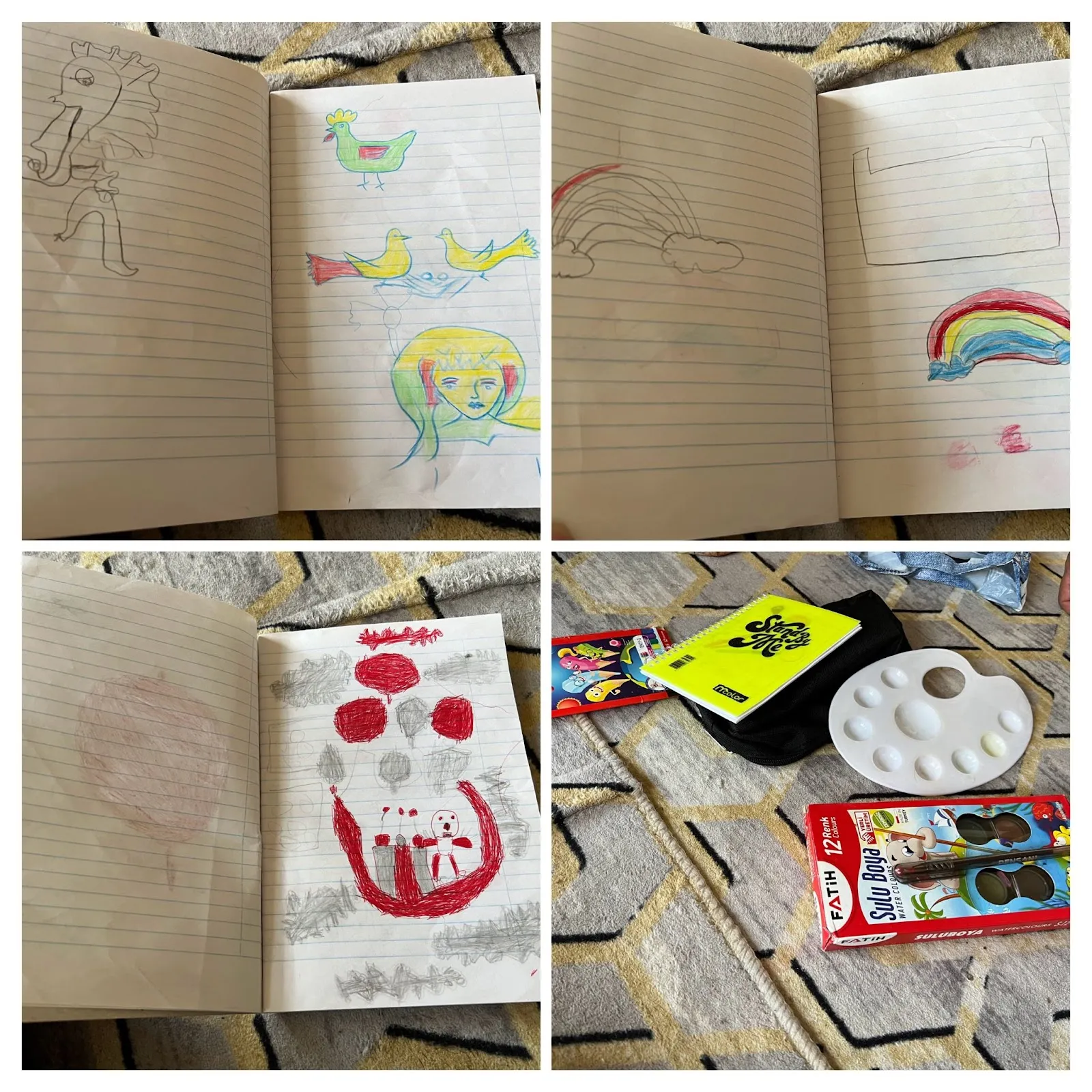

I didn’t want to be in between an eager child and his classes, so we skipped an interview and he scurried back to be with his peers. Instead, Ali showed me Mohammed’s favorite toy: a painting set.

Mohammed’s drawings, and, in the bottom right, his favorite toy – brushes and paint.

Mohammed’s drawings, and, in the bottom right, his favorite toy – brushes and paint.Mohammed still needs five surgeries, including a time-sensitive $1,500 surgery to help him regrow his hair on his burnt and scarred scalp. Doctors told Ali they have only two months to perform the surgery, or his ability to grow hair could be lost forever.

Among the many other reasons for the medical treatment, there’s a social one. Children can be especially cruel to one another, picking apart their peers due even to the slightest difference. And Mohammed’s scars have made him an outcast.

“The other children refused to play with him, due to the burns on his face,” Ali said.

His wife passed away after the Russian airstrike. Now all Ali and Mohammed have is each other, and the hope that they’ll be able to somehow find the resources to help him get his final surgeries.

“There’s nothing more important for me,” the proud father said.

https://counteroffensive.substack.com/p/the-other-russian-war-the-world-forgot?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=1547592&post_id=138990351&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=302pk5&utm_medium=email